It was the summer of 1977. Barbara Millicent Roberts wasn’t quite out of her teens when she accompanied my father and me to my first backroom poker game. I was a shy but precocious five-year-old who was along for whatever ride my parents were on.

My father was a mess of a charming man who elicited fealty through heavy-handed means or flat-out cheating—“the hustle,” as he called it. For him, there was no higher god than money, and between his joblessness and addictions, that god often fell silent. He pressed his luck at any high-stakes backroom table that might welcome him.

Often, he’d lose. But the hope of scoring always outweighed his more present realities, because he was an addict. Still, that summer he was on a particular mission, a determined effort to win back the down payment for a house (which he’d lost in an earlier late-night poker game). For weeks, desperation sat atop him like a circus tent, a new scheme hatching each moment.

More From Harper’s BAZAAR

I was nothing if not watchful. I paid attention to his moods and knew when he was plotting a hustle. I’d learned that when the adults started planning, my best bet was escape. My escape routes were infinitely safer than the world itself, and my favorite co-conspirator was Barbie. Every Barbie. We were the kind of family that didn’t have very much, but every Christmas my sister and I were each gifted with a new Barbie and her accompanying paraphernalia. We had everything from the Country Camper to the Star ’Vette to the iconic Dreamhouse. In my world of escape, I had many friends, and they all came out of a pink cardboard package with a cellophane window and box tether. There were Barbie, George, Ken, Skipper, Francie, and Christie. They’d whisper fantastic ideas and places in my ear, and were the kind of friends who let me work out my fears and desires through a story. And we—the lot of my dolls and I—performed our own type of careful plotting, which I called play.

Every now and then my father, sprawled across the couch, would look down at my amusements on the floor as I sat entirely enraptured by the Barbie-verse. I tried to pull him into my world in hopes that he, too, might find imagination a safer way to take flight from reality. I’d escape the quotidian for hours and be in a place where money was no big deal, where glamour and ecstasy were facts of life, and you could be in Malibu one day and space the next. Barbie enabled that easy kind of pretend play where time and space curved to create a different existence. My hours-long dalliances afforded me an elsewhere. All I had to do was to step into the ’Vette or the Country Camper with Barbie and be transported.

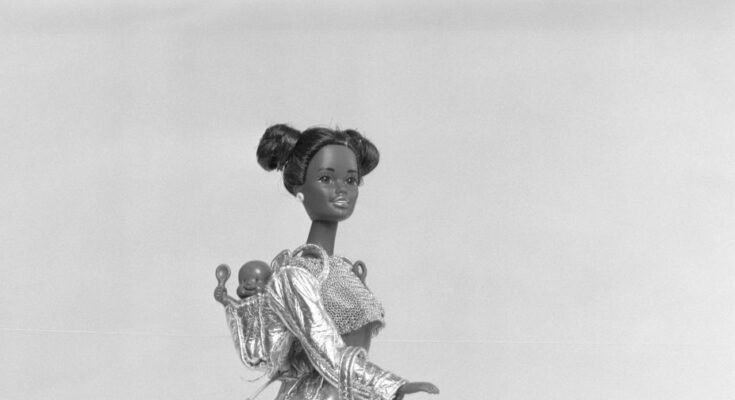

I knew the allure of ditching the now by opening the door to the Dreamhouse. “Look, this Barbie is a superstar astronaut who has discovered a planet of Weebles,” I’d say to my father as I reached to show him the statuesque Barbie as the leader of a group of indomitably stout egglike creatures who wobbled but wouldn’t fall down. If it was a good day, he’d smile at the rich dimensions opened to me and then retreat into the depths of himself. Although we would never play with my dolls together—a fact that Barbie and I eventually accepted—it was gift enough that he briefly welcomed my invitations to fantasy’s plausibility.

Mere weeks after he first showed interest, while Skipper and Barbie were taking the ’Vette to the Hundred Acre Wood in search of Eeyore, my father craned his neck to ask, “Baby, you and your Barbies ready to have your own room in a big house?” I nodded and gyrated my Barbie in an ecstatic circle. My father, the consummate hustler, had paid enough attention to my play to develop an elaborate ruse in which my dolls and I could be his spies at his midday backroom games. He figured that Barbie, through a series of gestures and manipulations, could indicate to him what the other men at the table were holding. I would only need to circle the table periodically, see the men’s hands, and pose Barbie into encrypted messages, helping him determine how much or how little to wager and, most importantly, when to fold. My father’s thinking was simple: A girl with a doll wasn’t an obvious ploy and was not a threat.

It took a solid month of intensive tutorials for my father to explain rank, the order of play, and the methods of betting that held his wonder. We made a game of jointly devising Barbie’s movements to signal information; it felt like a type of play. There were codes for the most important high hands. Rubbing Skipper’s chin or scratching Francie’s cheek, changing Superstar’s clothes, tightening the purple ribbon around Ballerina Barbie’s hair—each held meaning. My job was understood, and since Barbie was still smiling, I figured she was fine with it, too.

The gambit lasted a far shorter time than that summer’s heat. The work turned out to be a tall order for a five-year-old. Our signals continually crossed because Barbie would beckon me to play the way I wanted to play—and it was not at a smoky table of tormented men. In my last game, I pulled out my SuperSize Christie, meant to signal a full house. My father folded early and lost to a lesser hand—a terminal decision I wasn’t sure he ever forgave. But there were other instances of intentional slippage, miscommunication, short attention spans, and, finally, refusal. The fact is, I didn’t want to play with my Barbies according to my father’s conscription, and I resisted. Whether I was cracking an inside joke with Barbie about the men or in the bathroom asking her to help me get away, I chose that wild, pink-lipped rebel who didn’t require my nurturing or my complicity. Barbie only asked for my hand and led the way out of the profane into a magical terrain.

More than any other doll I ever played with, Barbie revealed the beauty of molding plastic into human form and unveiled the underlying impulse of play: to create an extension of the self, to articulate one’s will and to bend the body of limits. Magically, Barbie transmuted my childhood longing into a sweet nostalgia that still blows heavy. She reminds me of the imaginative intensity that children take on to push past time and space, or, perhaps, refine the ways in which they understand even their own capabilities. A child with a doll may seem disarming, but a child with an imagination is not. And while some may see her as a quaint relic of a long-past era, Barbie will forever be a dominant part of the American girlhood I somehow survived.

Writer

Airea D. Matthews is a poet and the author of the collections Simulacra and Bread and Circus.